You shouldn't.

Sort of.

Well, let's start at the beginning.

First of all, what is a main idea? Tim Shanahan has written at length about it here, but for our purposes we'll define it as the big ideas an author is trying to convey, whether in a section of text or an entire work. It's different from a gist, in that a gist is a first initial reaction to what you think a chunk of text (or the text as a whole) is about, while a main idea is the actual idea an author is communicating. Your gist may not be correct at first, because it's a surface-level skim of what a text is about, but the main idea should be correct because it can only be determined after a careful analysis of the text in question. (I've blogged about the difference between gist and main idea here.) In general, it's synonymous with central idea. And, in general, its counterpart in literature is theme.

(Let me issue a word of caution about getting too granular with the standards. These aren't legal documents, and we shouldn't approach them legalistically by making fine distinctions or closely analyzing the words. It's also important to know that these terms are treated very broadly and often interchangeably in the materials students will encounter. So, it's best to keep these terms more general for kids.)

Second, what is a main idea NOT? (Bad grammar, I know, but let's go with it.)

Determining the main idea of a text is not a skill that can be learned, mastered, and then applied to a different text.

There is no research that supports that idea that there is such a thing as a set of transferable "comprehension skills" that can be mastered and then applied with a new text. And our standards tend to be treated just like that ... a list of skills to be mastered one at a time, with the idea that once kids can do these things, they will be prepared to use them to understand other texts. (Strategies are another thing - though not too different - and I'll tackle that topic in another blog post.) Thinking about main idea specifically, we can encounter an author's big idea in really different ways in really different texts; determining the big idea an author is saying isn't a highly repetitive act, and there are no tricks to make it repetitive.

If I'm being REALLY honest, that idea blew me away when I first encountered it, and I rejected it because teaching comprehension skills is what I had been told to do - by my professors in my program, by the basal materials I used early in my career, and by some well-meaning literacy folks I turned to. And as a profession, we've been teaching this way for a very long time ... some 30 years or so. But we've got about 1/3 of our kids nationally reading on grade level, and we've been there for about ... 30 years.

When I thought about it, this idea confirmed what I saw in my own classroom. When I would get some set of data back, I'd typically identify my lowest standards and focus heavily on those specific ones, treating them as "skills." We'd practice them repeatedly until I thought they had it. But when it came to testing time and a fresh, long, and complex text, they never did, because it's not a skill that can transfer.

So, why do we even talk about determining main ideas or central ideas or themes? Well, because if a student can tell us the big idea an author is trying to convey, that's a very good indicator that the student has a certain level of understanding about the text that they are reading. (That is, after all, the whole point of what we're doing.) And the role of standard 2 is to help us understand how deep or how sophisticated that big idea should be when we hear a student share it.

Let me give you an example I've heard recently. A teacher was teaching with a text about World War I. A student was really struggling to determine the main idea of the text, and so the teacher sat and worked and discussed and taught. Finally, that student was able to select the correct main idea and supporting details. Then, the teacher asked, "So, what was the primary cause of World War I." The student looked back and replied, "I dunno."

But guess what. That had been the main idea! The main idea of that text had been the primary cause of World War I, and the student had (finally) been able to determine that ... but then he had completely missed the point and an understanding of the text. Could he find that main idea? Maybe. Had he understood what the author was trying to say? Certainly not.

So, what to do?

There are some research-based ideas that we can use as guidelines to help kids comprehend complex texts better, and as a result be able to understand the big idea an author is sharing. Borrowing from Shanahan, here are 5 big ones:

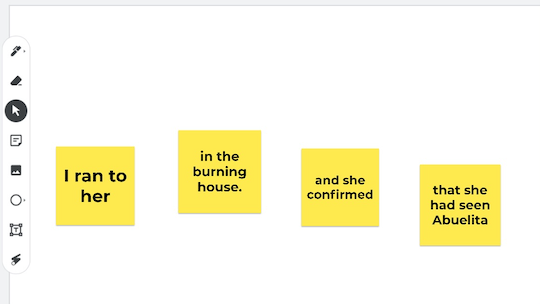

1. Teach students to find the gist and summarize. This is a strategy that has a good bit of research behind it. And if you think about your own reading, when you're absorbing something meaty and complex, you likely stop every now and then to think about what you've read so far. I've even borrowed professional books from friends who write their own quick synopsis at the end of each chapter. If we can summarize a bit, we are getting closer to that key idea an author is sharing.

2. Chunk it up. Start by summarizing a paragraph or few first, showing kids how to identify the important ideas, delete trivial or repetitive information, and paraphrase the key point in a single sentence. Then, move to longer chunks of text.

3. Use gradual release of responsibility. Model how you think about a paragraph, cross out trivial information, paraphrase, and think through to the essence of what an author is trying to communicate.

4. Read this way widely. Vary the text type, topic, difficulty, length, etc. Give them lots of practice to think in big idea ways, always asking, "What is the author trying to tell me here?"

5. Rank the ideas. Any text at a complexity for 4th grade and above (and often lower) will have multiple main ideas. As students think about these big ideas an author is communicating through their work, have them rank them in order of importance to the text as a whole or the quality of the evidence that an author is using to support it, explaining their thinking and their reasoning.

And always, always, always focus on making meaning of the text. The whole point of literacy instruction is to prepare students to glean knowledge or understanding from a fresh, complex text independently. We want them to constantly ask themselves while they're reading, "What's important here? What's the author saying to us? What am I learning? What is important for me to remember?" The more kids get the chance to do these kinds of things with a whole lot of different texts, the better they'll do overall.

Because it's not that we teach them to determine the main idea so they can understand the text. We teach them to understand the text so that they've understood the main idea.

Want to read more? Check out Tim Shanahan's blog post about teaching main idea

here and piece from Edutopia

here.

Here's to simply teaching well,